The impact of global warming on winemaking in France

- Categories :

- Wine

- Wine News

- Wine Making

- Gourmet Odyssey

Throughout the wine-making regions of France, the temperature is rising. For example, in the Bordeaux region, the temperature has increased by around 2°C during the vine growth period over the past 70 years. Climate change has been having a big impact in the vineyards for several years now, forcing the winemakers to reflect and change their working ways.

Together with warming, other extreme climatic conditions are threatening the vines. First to mind is the heat and drought that had such a strong impact on the 2022 vintage in all of France’s wine-growing regions, which also produced devastating fires in Aquitaine.

Milder winters cause the vines to burst into life earlier, increasing the exposure to spring frosts that can easily devastate the first buds. Hailstorms in the summer can do much damage, as can floods which spread disease in the vineyards… Each extreme episode hammers home the importance of protecting the environment. The wine-making world is one of the economic sectors that is the least climate sceptic, because each vintage is directly shaped by the changes in climate. The famous “normal year” that each winemaker talks about is becoming less and less normal.

How is climate change impacting the vines?

The development of the vines has evolved over the past few decades. We’ve already mentioned that the warmer winter temperatures are causing the buds to burst earlier and earlier, meaning that the buds are more exposed to spring frosts and for longer. The harvest period has also changed, and is now on average two to three weeks earlier than in the 1980’s.

Global warming doesn’t just influence the development of the vines, it also has an impact on the quality of the grapes and therefore how good the wine is. Many factors can have a bearing on the quality. For example, when there is a drought, the vines suffer from hydric stress. This causes less exchange of gases during photosynthesis and transpiration, provoking the vegetative growth to stop prematurely. It can cause the yields to be considerably reduced by having less grapes per vine and/or smaller grapes.

The increased sun and heat can also increase the sugar level in the grapes, making for less well balanced wines as they are more alcoholic and less acidic. The wine tastes flatter, is more unstable, less likely to age well, and more difficult to keep. Wines that are too strong in alcohol aren’t very well suited to today’s taste, and so wine-makers need to look for alternatives. In the wine-growing regions, the wines have risen by between 0.5 and 1° in alcohol per decade over the past 30 years. The wines are little by little losing some of their historic identity.

What solutions are available to fight against climate change in the vineyard?

The first solution is the change in wine-making practices that has already been evolving over the past few years. The winemakers have been forced to look at new techniques for pruning, irrigation, and surface management.

Château Cohola, located in the Rhone Valley has understood. The winemakers, Chéli & Jérôme, chose to structure some of their vines “en échalas”. Each vine is supported by a 2m high wooden stake, allowing the vines to grow up them. Once sufficiently grown, the tops of the vines are entwined with their neighbours, creating a natural parasol and providing shade to the grapes below from the sun. It also helps the wind to better circulate and dry the grapes in case of rain, helping avoid the development of fungi.

Regarding the frost, there are different methods available to protect the vines, but the most environmentally friendly way and simplest way is to delay the winter pruning. Traditionally, pruning started around December, depending on the region and size of the winery, but pruning is often now pushed back until March to delay the buds bursting and to protect the buds from the first frosts.

Château Coutet in Saint-Emilion suffered from the drought in the summer of 2022. Here another solution has been put in place. The use of small grass-cutting robots which cut the grass in the vineyards. This stops the soil from being too compacted and allows the vine roots to better penetrate the soil, dig deeper, and better withstand the whims of the weather. During a very dry year, the grass will compete with the vine, forcing the roots to dig deeper in search of water. During a rainy year, the grass will help limit soil erosion, and will make it easier for the water to penetrate into the ground thanks to its root system. The use of these solar powered robots can be adjusted in relation to the needs of the climate.

Some winemakers choose to irrigate their vines during dry spells. It’s not a very ecological solution, but some justify it by saying that its is necessary for the survival of their vines. Opinion is very divided, and irrigation remains banned or very strictly regulated for regions in France’s AOP system.

Some of these solutions might work today, but are they viable in the long term?

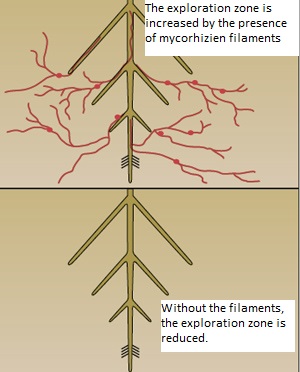

A very interesting idea is to encourage the development of mycorhizien mushrooms in the vineyards. The vines and mushrooms work together symbiotically. The mushrooms collect water with their long filaments that can cover a surface area of between 40 and 100 m² pour each 1m² and transport this water to the vine roots. In exchange, the vines give the mushrooms CO² from the photosynthesis.

Some winemakers want to take more radical action and are looking to find the equilibrium between the climate and the vines by using new grape varietals. Sometimes long forgotten varietals, sometimes from another warmer region, or a hybrid to produce vines more resistant to warmer climates. But careful reflection is needed. It’s not as simple as it sounds because the AOP system doesn’t give much flexibility in the rules governing how a wine is to be made. The AOP charters are very strict, and any changes take many years of study before being validated.

Legislation is bound to change though, and in 2021, the request from the Bordeaux and Bordeaux Supérieur appellations was validated by INAO to add 6 new grape varietals to the existing 13 Bordeaux ones. This change will allow the winemakers to use varietals more adapt to resisting global warming and disease.

Here is the list of new grape varietals allowed. (Source : bordeaux.com) :

Red grape varietals:

- Arinarnoa (origin INRA, 1956): Made from a hybrid of Tannat and Cabernet Sauvignon. Low sugar production, good acidity. Gives well structured, colourful, and tannic wines with complex and lasting aromas.

- Castets (origin south west France): An historic grape varietal, forgotten in Bordeaux. Resistant to grey rot, odium, and mildew. Allows to make colourful wines for keeping.

- Marselan (origin INRA, 1961): A hybrid between Cabernet Sauvignon and Grenache. A late developing varietal, resistant to grey rot, odium, and mites. Enables making colourful wines with character, of good quality and the potential for ageing.

- Touriga Nacional (origin Portugal): A very late developing varietal that is less at risk from spring frosts. Resistant to fungal diseases with the exception of dead arm wood disease. Makes very good quality wines that are complex, aromatic, full-bodied and good for ageing.

- Alvarinho (origin Iberian Peninsula): Marked aromatic characteristics that counterbalance the loss of aromas due to global warming. Resistant to grey rot. Medium sugar potential that enables the winemaker to produce subtle and aromatic wines with good acidity.

- Liliorila (origin INRA, 1957): Like the Alvarinho, it has good aromatic qualities giving powerful and scented wines.

Many studies of new grape varietals are underway in other wine growing regions. The changes will take many years, but the wines are set to change little by little.

What will happen if the climate situation doesn’t change in the next few years?

If the situation stays the same, we’re looking at +3 to 5°C between now and 2100. Greenpeace conducted a study that shows that to continue producing wines, the vineyards should move 1000 km to the north in the northern hemisphere and 100 km to the south in the southern hemisphere. That means that some of the best wines could be produced in countries such as the United Kingdom, Norway and Denmark. These countries are already producing wines, and in the last 40 years, the United Kingdom has gone from just a handful of wineries to over 700 today.

We hope that by 2050 the temperature rise will have stabilised below 2°C thanks to the engagements undertaken at the COP21 and that we will still be able to enjoy France’s great wines because the winemakers will have managed to adapt to the rising temperatures.

Comments

No comments.